The Nigel Balchin Newsletter

Issue 7: February 2013

Welcome and Introduction

Welcome to this issue of the Nigel Balchin Newsletter and an especial welcome to those new subscribers who have joined up since the last issue—I hope you find something here to interest you.

I am pleased to announce that the Nigel Balchin Website (www.nigelmarlinbalchin.com) is currently undergoing a (long overdue) update and makeover. Its appearance will be changed quite substantially and I am also incorporating a lot of new content. I am sorry that the site has remained largely unchanged for so long—I do have a passionate loathing of out-of-date websites and I know that I have been promising big changes for quite a while now but all my efforts in 2012 were directed towards finishing my biography of Balchin and the website was consequently shunted down my priority list. But the revamped site will soon be up and running and any comments or suggestions for additional improvements will be gratefully received.

One little piece of housekeeping to finish with. I’ve decided to subtly realign the publication schedule for this newsletter and so henceforth it will be published at the beginning of the following months: March, June, September and December. I will therefore be back with the next bulletin in early June.

Did You Know?

News has reached me recently that one or two American publishers are expressing interest in reprinting some of Balchin’s novels. If any of these plans come to fruition then I will of course update you all via this newsletter. Will we one day see a comprehensive Balchin reissue programme in the UK, say of six to eight of his best novels? It seems unlikely at the moment but I remain hopeful that some sort of reissue programme will get off the ground within the next few years. Fingers crossed…

Making a Good Beginning: An Analysis of Nigel Balchin’s First Three Novels

Introduction

In the last issue of this newsletter I looked at what I described as Balchin’s ‘Big Three’, namely the trio of novels he wrote during the Second World War that made his name as a writer. This time around I want to focus on the first three novelsofBalchin’s career, analyse their strengths and weaknesses and, by doing so, tell you whether you need to read them or not!

By the middle of the 1930s Balchin had written a number of plays and short stories, without much success. He began writing his first novel (and rumour has it that this took place on his honeymoon in Cornwall in 1933) because, as he put it, “I had a story which I wanted to tell which for some reason I felt went into the novel medium more easily than into the play medium or the short story medium.”

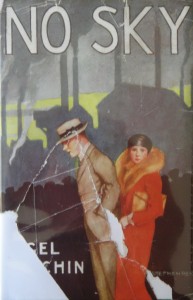

“A good beginning” – No Sky (1934)

What is it about?

No Sky, Balchin’s debut novel, tells the story of a Cambridge medical student who is forced to abandon his studies and go out to work when his father dies suddenly. He obtains a position in the time-and-motion department of an engineering factory but soon finds himself imprisoned by the job and trapped in an inadvisable marriage.

Where did Balchin get the idea from?

He was extremely familiar with the factory environment as a result of his work as an industrial psychologist in the first half of the 1930s.

What is it like to read?

Although very different in style from the likes of The Small Back Room, No Sky is well written and extremely easy to read. It is wordier than Balchin’s later novels, with less dependence on dialogue, and contains lengthy descriptive passages that he didn’t indulge in once he had tasted success as a novelist. The characters are not particularly finely drawn but the situations are convincingly delineated and the book is very well observed.

The main fault with No Sky is that it is simply too long. Also, as the book approaches what should be a resounding conclusion, Balchin puts undue emphasis on the romantic subplot, to the obvious detriment of a much more interesting confrontation that is brewing in the factory. As a result, the story fades away very tamely.

Apropos of the style in which the book is written, Balchin said of it that “I tried to write in sentences and phrases instead of using words. […] I was self-conscious about the style”. This quirk has never been that apparent to me but I suppose the writing could be said to be a bit mannered in places, and certainly light years away from the clipped urgency deployed in Darkness Falls From the Air, A Sort of Traitors and Sundry Creditors, for example.

How did it fare in the bookshops?

Ralph Straus,perhaps the leading literary critic of the day, said in the Sunday Times that “Mr. Balchin has made a good beginning; you can believe every word in his book” but elsewhere in the national press No Sky was scarcely reviewed at all. Perhaps not surprisingly therefore, sales were very sluggish. Balchin claimed that his debut novel had sold “about 600 copies” but that may well have been an overestimate.

Do I need to read it?

I think you can get away without doing so! No Sky is interesting and amusing in places but unless you are a devoted student of 1930s time-and-motion procedures (which are at the core of the book) then I think you can safely give this one a miss. You will struggle mightily to get hold of it even if you do want to read it. Largely because of the poor sales mentioned above, it is exceptionally difficult to find a copy to buy. I bought one on the internet about seven years ago but have not seen any others advertised for sale subsequently. If you feel that you really have to read No Sky (and you live in the UK) then your best bet is to join a legal deposit library such as the British Library in London or the Bodleian Library in Oxford.

“A graphic and interesting book” – Simple Life (1935)

What is it about?

Balchin’s second novel concerns a young advertising copywriter living and working in London who is fed up with his job and his fiancée and so decides to ‘go native’ in Wiltshire instead. He muscles in on a couple of ‘simple lifers’ who are residing in an isolated cottage and tries to fit in with their way of living, with very mixed results.

Where did Balchin get the idea from?

The author had worked with J. Walter Thompson a few years before when he had been involved in the launch of Black Magic chocolates and this helped him to paint his portrait of the advertising agency depicted in Simple Life. As a child growing up in Wiltshire, Balchin was very familiar with the countryside in the vicinity of Salisbury Plain, which is where most of the action takes place.

What is it like to read?

Well it’s a definite improvement on No Sky. The writing is more confident and assured, the book contains lots of interesting ideas and the early chapters are often very amusing. The characters in Simple Life are more lifelike and well rounded than those in No Sky and Mendel, the monstrous egotist who dominates the second half of the book, is the first notable character in Balchin’s fiction.

Simple Life possesses many of the same faults as No Sky. Again, it is too long and it gets bogged down in philosophical discussions from about its midpoint onwards. I also think that the ending is rather weak and unconvincing.

When he reviewed it in the New Statesman, Cyril Connolly described Simple Life as “a graphic and interesting book” and that’s a fair enough summation. However, I should point out that Connolly favoured the second, philosophical, half of the book, whereas I prefer the witty satire of advertising and country life to be found in the opening chapters.

How did it fare in the bookshops?

Probably about as well as No Sky. It almost certainly sold hundreds, not thousands, of copies. It was never reprinted and, like its predecessor, remains extremely hard to find in second-hand bookshops or on the internet.

Do I need to read it?

Simple Life is a more important novel than No Sky. It saw the introduction of a love triangle into Balchin’s fiction for the first time and it is also a prototype of his take on the novel of ideas, preparing us for later examples such as A Sort of Traitors and A Way Through the Wood. Although, like No Sky, it is consistently readable, with notable high spots along the way, it does become a little tedious after a while. The novel’s central theme—escaping from the rat race—still seems relevant today but this is very much a book of the 1930s about the 1930s. Therefore I think you can afford to skip this one too without feeling that you have missed out on something vitally important!

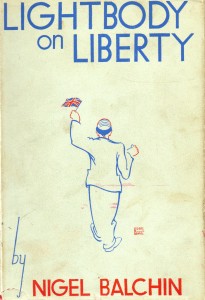

“A gorgeous book” – Lightbody on Liberty (1936)

What is it about?

A mild-mannered grocer considers that he is a victim of police persecution. Having been arrested and then bailed he becomes the unlikely standard-bearer for a nationwide campaign against petty restrictions on the liberty of the British people.

Where did Balchin get the idea from?

As his father was a small shopkeeper in Wiltshire, Balchin certainly knew about the grocery business. The ‘liberty’ theme appears to have emerged out of his own head but Balchin was a keen student of current affairs in the 1930s—and, I believe, an ardent newspaper reader—so he may just have been reflecting contemporary concerns about restrictions on people’s freedom.

What is it like to read?

Unlike anything else Balchin ever wrote! The central figure Alfred Lightbody is, uniquely for Balchin, a working-class character and as the author strove to make his speech as lifelike as possible (dropped aitches, etc.) it makes the book look completely different from all of his other novels. Having said that, it is not difficult to read at all and one soon gets used to the unusual speech patterns.

This third novel of Balchin’s nascent career contains several notable characters. Top of the list is Lightbody’s son Bert, a young Communist who maintains a highly entertaining running commentary in the early chapters on what he laughably believes to be his father’s bourgeois pretensions. Sir Joseph Steers, the millionaire philanthropist with the volcanic temperament who backs Lightbody’s campaign for liberty, is also good value.

The novel is full of interesting and potentially hilarious situations but somehow Balchin never quite succeeds in fully exploiting them and so the book raises the occasional titter only, when frequent outbursts of belly-laughter should surely have been the order of the day given the material at his disposal. As Balchin’s sole attempt to write a genuine comic novel, Lightbody on Liberty has to be rated a failure.

Once more, the book is much too long and it peters out limply at the end. In his excellent survey of Balchin’s fiction (http://www.clivejames.com/pieces/hercules/balchin), Clive James remarked that Lightbody on Liberty could have been ruthlessly boiled down and then used as the basis for an Ealing Studios/Boulting Brothers-style ‘comedy of disillusionment’ and that’s a very astute observation.

Despite all these provisos, I’ve always had a sneaking regard for Lightbody on Liberty and it is probably my favourite among Balchin’s pre-war books. It is very well written and fun to read. So long as you don’t expect it to be side-splittingly funny then it is unlikely to disappoint.

How did it fare in the bookshops?

Gerald Gould in the Observer said that Lightbody on Liberty was “a gorgeous book” and the reviews as a whole were very favourable, which must have stimulated sales. Although I succeeded in finding sales figures for most of Balchin’s novels I didn’t come across any for his first three. James (who had access, in the early 1970s, to information that would no longer seem to exist) said that Lightbody on Liberty had sold “in the thousands” but, if so, I would guess that the number of volumes shifted by the nations’ booksellers was at the lower end of that range, i.e. closer to 1000 than 10,000.

Do I need to read it?

No, but if you are going to try to read any of the books featured in this article then this is probably the one to go for. Simple Life may be more important to Balchin scholars but Lightbody on Liberty is more rewarding and it has the virtue of unusualness because Balchin never wrote anything else like this throughout his long career. (By contrast, No Sky is rather like a dry run for 1953’s Sundry Creditors and Seen Dimly Before Dawn, with its love triangle and rural setting, revisits some of the territory explored in Simple Life.) Crucially, you are more likely to be able to find a copy of this book than the other two because they do surface on the internet or in second-hand bookshops periodically.

Conclusion

Balchin’s first three novels may lack the enthralling quality of his later work but they are all intriguing curiosities. No Sky has an interesting ‘men at work’ theme, Simple Life saw Balchin put in place some of the major preoccupations of his mature period and Lightbody on Liberty is a warm and enjoyable read. Perhaps the most interesting thing about Balchin’s opening trio of novels is that they were written in a completely different style to anything he wrote subsequently: I am willing to bet that if I ripped the covers off one of these books so as to anonymize it and sent it to someone who had only ever read The Small Back Room or Mine Own Executioner then quite possibly they would never guess it had been written by the same man!

Further information on all three novels can be obtained from the website (www.nigelmarlinbalchin.com) and a guide to buying Balchin’s books appeared in issue 3 of this newsletter (email me if you would like to receive a copy).

Did You Know?

A number of Balchin’s works were given alternative titles for the American market. Thus A Sort of Traitors was retitled Who is My Neighbor? when it was released stateside and Sundry Creditors became Private Interests. The Fall of the Sparrow also had its title tweaked very slightly for U.S. readers, beingaltered to The Fall of a Sparrow. Balchin’s films didn’t escape the retitling process either. The Powell and Pressburger movie of The Small Back Room was changed to Hour of Glory for American release and Suspect (the Boulting Brothers’ take on A Sort of Traitors) was retitled The Risk in the USA. Note also that when A Way Through the Wood was (belatedly) filmed as Separate Lies in 2005 the novel was re-released in the UK by Orion Books under the film’s title. Finally, Balchin’s novels were translated into a wide range of foreign languages. Those linguists amongst you can amuse yourselves by trying to work out which English language versions the following titles started life as: Das Kleine Hinterzimmer, Mon Propre Bourreau, Reyes del Espacio Infinito, Les Revelations du Matin.

News of Progress With My Biography

At the risk of beginning to sound like a broken record, I have to report that I have still not quite finished writing my biography of Nigel Balchin. I have been working extremely hard at revising the text for the last six months or so and have made a tremendous number of improvements in that time but there is still a bit more to be done before I can call it finished. At present, I am rewriting a small number of chapters towards the end of the manuscript that I felt were sub-standard. This is time-consuming and frustrating for me of course but it’s just one of those things that I have to do in order to ensure a high-quality end product. I will not be truly happy with the book until I am proud of what I have written from first page to last. So, as the critic Benny Green said about “the battle which Sammy Rice wages against himself” in The Small Back Room: “The struggle goes on”!

I think I will stop making predictions in this column about exactly when I will finish the book because I never seem to stick to them! However, there really isn’t too much more remaining to be done now and I will of course let everyone know just as soon as it is finished once and for all.

Thanks for your patience!

Best wishes,

Derek (backroomboy@talktalk.net)

STOP PRESS!

Those in the Birmingham area of the UK on Saturday 9 March might like to spend an hour or so in Stourbridge that afternoon. An organization known as Kaleidoscope that is dedicated to the study of vintage television programmes is staging a festival called Rediffusion Rewind. Rediffusion, an independent television channel that broadcast in the London area in the 1950s and 1960s, put out an adaptation of The Fall of the Sparrow in 1965 plus a number of the Uncle Charles stories two years later. As part of their festival, Kaleidoscope will be showing the ‘Gentle Counsels’ episode of the Uncle Charles series. Not shown in the UK since the late 1960s, I think it will be well worth a look. The event is free and full details can be obtained from the Kaleidoscope website: www.kaleidoscope.co.uk. I’ll include a report on it in the next issue.